Dispatch from AZLANA

Azlanan riviera; winding promenades; mythmaking in art; burial taxes; and more!

Time to get back to it! Azlana is the neighbour of my homeland, Nicaragua, and the historic rivalry between the two nations is well known. Tensions have mostly simmered down these days, but it is still quite uncommon for Nicaraguans like myself to visit—all the more reason to see the country now for myself. ¡Vámonos!

DISPATCH

The harbour of San Blas bathed in sunshine was a sight to behold. Once a critical naval port on the Pacific coast of New Spain, it is now a surfing haven and beach getaway for Hollywood stars.

On the SS Quezon, we were told that San Blas is one of the last ports in Columbea to still receive oceanliners from Manila. Prior to Partition, it would have been the penultimate port of call for the famed Manila galleons. The iconic terminus, Acapolco, is now in Nicaragua, and in its postcolonial pivot, seems to have not maintained its ties with the rest of the Hispanosphere like Azlana.

Contact with the Miniras, the Galeras, and beyond has left an indelible footprint on the culture of San Blas. Strolling its streets, we overheard tongues as diverse as Hawaiian, Philippino, Fernandino, and even Kantonese. Illustrating this deep connection, we stopped to get yuqui—shaved ice dessert flavoured with syrups—a delectable dessert introduced from Japan in the 19th century. Back in Nicaragua, I would always get it with chamoy syrup—itself an introduction from Kanton—and alguashte, which we call ayotl achtli, “(pumpkin) seed juice". Imagine how I felt seeing Azlanans also enjoying the same flavour. I could not pass on the opportunity to order it here.

We had spent enough time at the beach in Towaii, so we didn’t stay to linger in San Blas. We took the express train to Santa Fe, the capital, where we met with representatives of Azlana’s newest tourism campaign. I won’t bore you with the details of our work and meetings, but needless to say, Azlana has some of the greatest potential in tourism opportunities in all of Septentrea. Already a transportation hub of the region, they have long been overshadowed by their historic rival, Nicaragua, when it comes to soft power and cultural appeal to international tourists.

With the 2026 World Cup looming like the Sword of Damocles, many in the country feel like this is a make-or-break moment for the tourism industry. Everyone is hoping to make a good impression. Our job with the Slow Foot Movement, it seems, was to figure out ways to expand Azlana’s appeal to visitors from places that rarely come, like the Emporic Rim and most of Africa, and to get them to the sights beyond the coastal tourism hubs.

On our first morning off on our own, we got up early to chow down on chilaquiles, consisting of pulled chicken, eggs, cheese, beans, cream, and tomatillo sauce all sprawled over crispy leftover tortillas, the famed nixtamalized maize flatbread eaten in both Azlana and Nicaragua. The dish illustrates the fusion of Hispanic and Nicaraguan influences that shaped the cuisine in much of Azlana. Back in Nicaragua, the dish is mostly enjoyed in Christian restaurants, and even though this kind of food is just as much part of the country’s heritage, non-Catholics always label it as Azlanan.

We paired our breakfast with a cup of chocolate, the local way of drinking cocoa. This is more familiar to me, but Azlanans drink it with copious amounts of milk rather than water and spices, and they douse it in sugar. My parents would faint if they heard that I could appreciate this way of drinking cocoa as well!

Julisa Juárez Alvarado, one of the chief architects of the bid for the 2026 World Cup, came to meet us after. She would be our guide. Although Azalana has a good rail network, Julisa wanted us to take the slow route, which consists of taking minibuses. On the way, we got to explore the clean promenades and romantic squares of Leon and Nuevo Queretaro, but we were blown away by the historic city of Guanajuato, which happens to also be Julisa’s hometown! Despite its historic importance, Guanajuato is today off the beaten path. The city is not connected by high speed rail, which is an utter shame considering it is a hidden jewel for travellers.

Our hotel is a small bed and breakfast, staffed by a lovely older man, Don Albert Vonnegut, who immigrated from the Texas Hill Country some 20 years ago. In Spanish accented with traces of Texas Dutch, he gives us a tour of the historic building we are staying in. Though it now houses a hotel, it was previously a government building that housed the Spanish viceroy in colonial times. The most amazing thing is how it is literally across the road from the Plaza de la Paz, the central square housing the Basilica of Guanajuato. This cathedral is painted bright yellow and red, and it just radiates on a sunny day!

We meander up to the Guanajuato Museums Complex, which is a plaza containing several distinct museums within it! Our first stop is the Diego Rivera House Museum. Rivera was a famed Azlanan muralist who married Frida Kahlo, also of fame. Rivera, from long-standing elite heritage and Kahlo, a descendant of Partition refugees and recent immigrants, were two of the most consequential painters in shaping the way Azlanans perceived themselves. Though Kahlo’s home in Santa Fe is more visited by tourists from abroad, the Diego Rivera House Museum also hosts important pieces from both artists. It also showcases colonial architecture, as the house and original furniture are well looked after. Most importantly, we got to see Rivera’s most important artwork, Dreams of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda, which portrays the complicated mess of cultural convergences of the early 20th century Azlana.

Julisa explained to us that to many upper class Azlanans, Rivera’s imaginaries assaulted the old Hispanidad identity. Incorporating their southern neighbours and traditional enemies left unresolved tensions, especially for those who still hold onto tragic family histories set in the backdrop of Partition—including families like Julisa’s. But the new possibilities Rivera and Kahlo offered in their work cannot be understated. They were part of the movement to establish friendly relations between Azlana and Nicaragua, known as Pan-Anahuacism. Rivera even designed the National Art Gallery for Nicaragua, combining Nicaraguan and Art Deco styles.

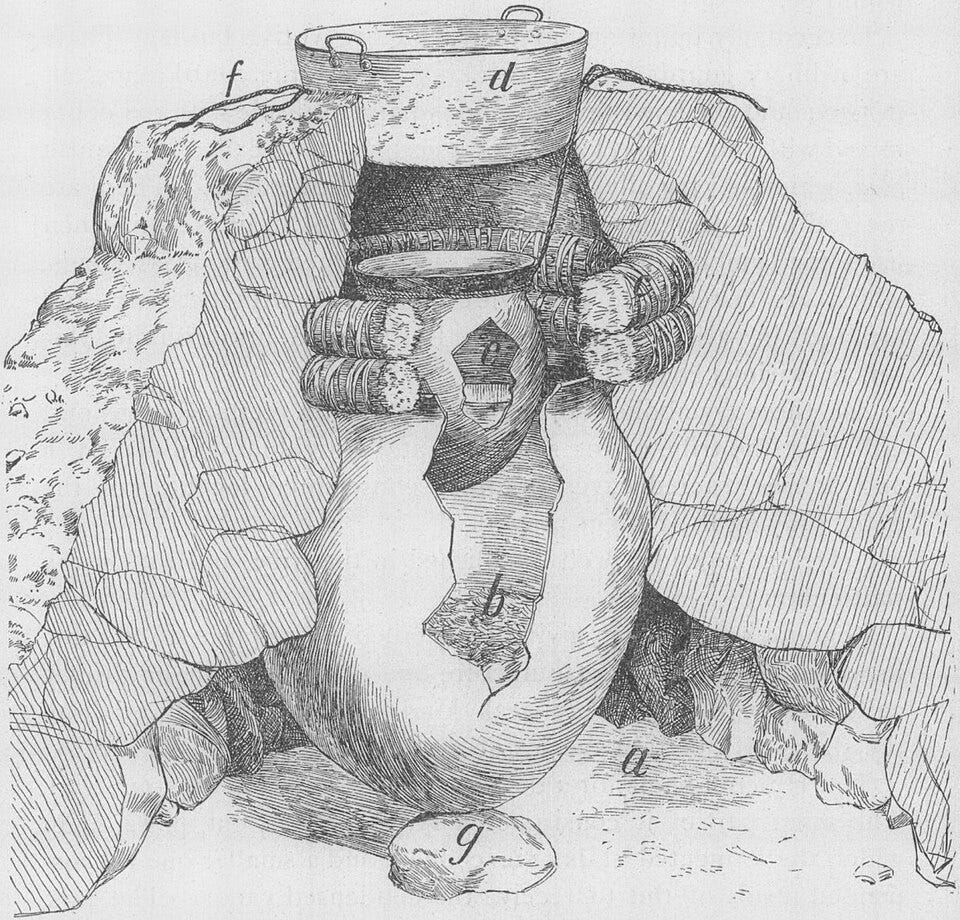

Our next stop was the Guanajuato Mummies Museum! Mummification is not usually associated with Azlana or any part of the largely humid region of Columbea. Because of Guanajuato’s dry climate, however, it can occur naturally. The city’s mummies are the result of a peculiar law, the burial tax of the municipal cemetery. Dating to the 1800s, the authorities figured that they could dig up the remains of those whose families did not pay the tax. As the corpses were preserved naturally, they stored them in a warehouse above ground until the fee was paid! Many fees were left unpaid…

This strange history led to many tourists from across the country coming to see the mummified bodies, and the groundskeepers would oblige for an admission price. The site was eventually taken over by the National Institute of Anthropology and History, but it remains as a curiosity many want to come see. The rest of the museum offers engrossing exhibits of local history, but it is clear that the mummies are the main attraction. Even the city’s local cempoala team is named after them. “I was terrified of that movie as a kid!” said Julisa, as we passed a framed original movie poster for the 1970s horror and adventure classic El Santo vs las momias de Guanajuato.

We made our way back to the hotel, pausing to listen to local hawkers in the plaza as the sun set. We slept in the next morning and took it slow as we wandered through the narrow streets of Guanajuato, loading up our cameras with lovely pictures of the colonial architecture here.

That same evening, we hit the road again, making our way to Leon to catch a sleeper train that would take us back to the Pacific coast. We arrived in Valdemoro, Sinaloa Province, before the break of dawn. From there, we took the famed sightseeing train known as the El Chepe Express. This train service has connected the cities of Valdemoro de los Mochis and San Felipe de Chihuahua. The train runs through a series of canyons known as the Barranca del Cobre, “Copper Canyon,” offering stunning vistas. “January gets real cold up there,” warned Julisa, holding up backpacks full of camping gear. “Luckily, I brought us wool fleeces!” The train takes 16 hours to complete its journey, slowing down to let tourists have countless chances to hop off to admire and take pictures.

In the train’s car, we enjoyed a proper Sinaloan dish for lunch—aguachile! Made from fresh seafood caught that morning, this dish is a relative of the more popular ceviche, and consists of shrimp, and slices of meat from chocolate clams and penshells, seasoned with lime juice, cucumber, onion, chiltepin pepper, and sometimes avocado and sesame seeds. Unfortunately, most tourists overlook this dish. The most popular Azlanan dish among visitors is the burro, known simply as taco in English due to the influence of the Nicaraguan Spanish—though here, wheat is the basis as opposed to maize in Nicaragua. “I am told travellers from Hawaii and Towaii travellers enjoy aguachile though,” Julisa noted. Having just come from that part of the world, we nodded enthusiastically to confirm!

We arrived at 4 in the afternoon at the town of Divisadero, and pitched our tents at a designated camp-site outside the village. As this is the coldest time of the year, there are few visitors, so we meet enthusiastic handicrafts salesmen. The locals here are mostly Indigenous—mainly Tarahumaran— and known for their textiles and turquoise jewellery. I bought a woven coin purse, and also a turquoise bracelet to mail to my partner in Cumbreland!

Early next morning, we met up with folks that Julisa knows well, the Ramírez Hernández family. They took us to the best view point to appreciate the sunrise. The hike through rugged country was a challenge, and we laughed at how we struggled to keep up with even the youngest of the family, who enthusiastically encouraged us the whole way—god forbit we miss the sunrise! Carmelita, the youngest among them, also made sure to educate us on local flora and fauna!

Though many of their relatives now live across the border in the Tarahumara Ejido of Arizona, Ofelia, the mother of the family, told me that their community entrenched themselves up in these high mountains and deep canyons to resist colonial pressures even after Partition. Tourism in Barranca del Cobre initially led to displacement of the Tarahumarans of Azlana, but local activism in the 1970s made it possible to resist most attempts of displacement and allow locals to even develop ecotourism initiatives instead. I smile thinking about the effects, as this is the positive impact we hope to promote with the Slow Foot Movement—tourism as a means of inclusion, not exclusion! I understand now why Julisa brought us here, and I thanked Ofelia and Carmelita for sharing their knowledges and experiences with us.

The next day, we bid farewell to the Ramírez Hernandez family, who made us promise to visit again some day, and we boarded the train to Chihuahua. With our time in the country running out, Julisa insisted we could not leave without first trying the diverse liquors of Azlana, so we checked into our hotel and after quick showers headed back out to enjoy the nightlife. Most people only ever have tequila, and while that type of spirit is deserving of its fame, there is so much more. Julisa explained that there are two types of spirits made from aguamiel, the nectar of succulent plants. There’s mezcal, spirits made from the aguamiel of plants in the Agave genus, and sotol, spirits made from the aguamiel of the bushy palm-like plants of the Dasylirion genus.

Alcoholic beverages have been produced in this part of the world since time out of mind, but distillation was introduced during the colonial era of New Spain. It is the perfect synthesis of cultures brought together by empire. We were pleasantly surprised to learn that the technique came via the Manila galleons, which brought over thousands of settlers from the Philippines, who shared their knowledge of using stills to make potent liquor with Spanish and Indigenous peoples here. Today, Azlanans pride themselves in preferring the many spirits developed in that time, as opposed to the people in Nicaragua and Arizona, who still more readily drink the undistilled boozes traditional to their locales.

Over the course of the night, we tried perhaps a dozen spirits. Our favourites were raicilla and cucharillo, plus the the northern specialties of bacanora and palmilla. Sotol is not well known outside of Azlana, but one of Chihuahua’s points of pride is the foodways they developed with arid crops such as the various Dasylirion plants. Today, its sotols have protected status. If I were to pick between them, I think I will go for a well produced sotol over mezcal, preferring the earthier and piney taste of the former over the smokey sugariness of the latter.

At the end of our bar crawl, we could think of no better way to cap of the night than to get burritos, the icon of northern fare. Though this time we didn’t get to visit their origin in Juarez, burritos are available everywhere in the north. Filled with nipa or rice, and refried tepar beans, as well as meat and spicy salsa, these hefty wraps did us a favour for our hangovers the next day!

The next day, we parted ways with Julisa at the train station. She was headed for home, while we were headed down to the big city of Monterrey for a some more work-related matters and to plan and recuperate for our next move. Knowing that we had taken to their way of consuming cocoa, Julisa stuffed into our bags some instant chocolate. “Just call if your itinerary lines up with one of the World Cup venues,” she told us. “I’ve got VIP seats waiting for you.” And with one final wave, we parted ways.

FIELD NOTES

Azlana’s flag is a holdover from the First Nicaraguan Empire, being the flag of Emperor Agustín de Iturbide. It has three diagonal bands of white, green and red, and while the colors do not have an official meaning, the three golden stars in each band do. They represent the unmovable principles known as the Three Guarantees of the Plan de Iguala—unity of the nation, the Catholic faith, and independence from Spain. Despite the fall of the First Empire just decades after Independence, the First Republic of Azlana adopted the flag after Partition, and it has remained the same ever since despite changes in government and even the relationship between the state and church.

You cannot truly understand Azlana without knowing the importance of Catholicism to this country. After all, the Partition two centuries ago was based on religious lines. The division led to two separate states, the Republic of Azlana and the Union of Nicaragua—at first including the ejidos of Arizona—supposedly offering a Catholic homeland and safe haven for Hispanicized peoples largely found in what we now call Azlana. For centuries, life in this part of the Spanish Empire was organized around churches, missions, and Sunday mass. Priests held a lot of land and power. The elites of the country were largely in favour of this arrangement, and life continued unchanged until the French Intervention of the 1870s.

Once the French were kicked out, Azlana entered a 70 year period of history known as the Cientificato, which roughly translates to the Technocracy. Led by educated aristocrats inspired by classical philosophers, the nation industrialized and secularized rapidly. Catholic priests lost power despite the nation still emphasizing its Christian heritage in opposition to the identity of its rivals across the border. Ironically enough, this period coincided with the rapid growth of the Galerist faith of the marginalized coastal communities, which was at first forbidden by Catholic priests.

Though most Azlanans acknowledge they have at some pre-Hispanic roots, the Cientificato built a national identity founded on the supremacy of Spanish heritage, which was not questioned until recent times. In many ways, the country is still reeling from the discriminatory policies of this period. The economic system impacted peoples and parts of the country unevenly, with the central Bajio tract benefitting the most. Only the mass general strikes of the Great Depression, ironically led by priests who espoused liberation theology, broke its yoke. Azlana has since moved away towards a democratic welfare state model, and anti-clerical sentiments have subsided significantly.

Today, life in Azlana is quite prosperous. The heavy industries that powered the country’s transformation still exist in the northern provinces of Guerrero and Chihuahua, but a lot of the population has changed over to working in the service sector. In the provinces of La Chichimeca, Coahuila, and especially Sinaloa, agriculture and fisheries are still dominant. The country is connected by high speed rail to California, America, and Liberum and the countries between them.

The national language of Azlana is Spanish, but the variety of Spanish spoken here has significant loans from both living Indigenous lects like Tarahumaran and Metec, as well as classical ones like Nahuatl and Purepecha. Azlanans can pronounce consonants other Spanish speakers cannot. The most obvious one is the /t͡ɬ/ sound, the infamous sound at the end of many Nahuatl words. Rather than pronouncing it how most Spanish and English speakers do, Azlanans will direct the air through the sides of their tongue and will not vibrate their vocal cords. As the sound is hard to master by outsiders, it has become a shibboleth of sorts. The endonym of the country, Aztlán, for example, is pronounced this way.

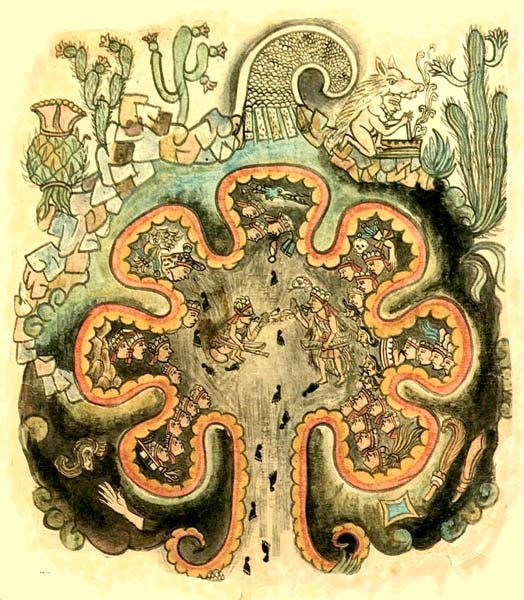

Speaking of the country’s name, Azlana derives its name from the mythic ancestral homeland of the Mexihca and Tlaxcaltecs, Aztlán, where the seven Nahua nations emerged from seven caves, the Chicomoztoc, before some moved south to the fertile valley of Mexihco in modern Nicaragua. Because of the importance of this tale to the wider region, the First Republic of Azlana adopted seven stars on their national seal to represent the caves. The semi-nomadic nations who stayed north were called the Chichimecah, making their home in what we now know as the Bajio tract of Azlana. and they came to be regarded as the “barbarians” in the eyes of the settled Nahuas of Mexihco, who, ironically, are also known as the Aztecs.

Most Azlanans are in fact mestizos or of mixed heritage. People of predominant European, African, Serican, Sumatrean, and Indigenous ancestry are also common, especially outside of the cities and Bajio tract. Along the populated border with Nicaragua, there is little physical and genetic difference between Azlanans and Nicaraguans. Today, more and more Azlanans and Nicarguans are recognizing this, as new research, political dialogue, cultural exchange, and other initiatives are slowly helping to heal over the old divisions born out of colonialism.

Local fare in Azlana includes staples of pre-colonial cuisines, such as maize, haricot or common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), tepar (Phaseolus acutifolius), as well as nipa (Distichlis palmeri) and rice and wheat. Nipa is a wonder crop, having been domesticated first by Indigenous people in Arizona and then further bred to be become a major staple across the world under the Spanish. It is grown in the salt marshes, coastal estuaries, and arid upland areas of the north. Spanish introductions like queso or fresh cheese, as well as cream, is used on almost everything, and beef is as popular as pork and chicken here. Like their neighbours in Arizona and Nicaragua, Azlanans need spice or the addition of chile peppers to their foods, though perhaps to a lesser degree. If you do come visit, I recommend leaving the beaten path and stopping to taste authentic cuisine that is not tailored to tourists, as it will be significantly more flavourful and will pack a punch! And remember, though Azlanan cuisine is very popular in America and the West, most “Azlanan” fast food restaurants overseas will instead serve you Texan cuisine, which is probably most similar to northern Azlanan food due to their historic connections—just calibrate your expectations, as it might be different than what you are expecting but is very much worth it!

azlanan fast food places selling texan food is hilarious

Wow that was an amazing read. I looked up Guanajuato on google maps and was delighted by the tunnel road system. It was the firs place I randomly dropped in on streetview. The cameras dont do too well in the low light but I'd never thought of underground crossroads. It blew my mind. Thankyou for bringing us on the journey CC Winter <3