Dispatch from THE PESCADORES

Painted houses, kissable cods, swimming caribou, baby goons, and more!

What a way to arrive at our next destination! We arrived on the austere shores of the Pescadores feeling like winners—having enjoyed amazing tablecloth dinners all week, getting to catch glimpses of beautiful icebergs in the distance and fin whales up close, and of course, having won some extra cash at a chess tournament on the upper decks of the SS Margrethe II. We got off when the ship called on the port of Donibane, the largest city in the country and famous for having one of the most naturally protected harbours on this side of the Atlantic.

Let’s see what this remote yet popular destination of the Secidades has in store for us!

DISPATCH

Wow, we really had our work cut out for us in the Pescadores … This tiny windswept nation holding onto the rocks at the edge of the Septentrean continent is a powerhouse of tourism. There is such a thing as too much of a good thing, however, and that is where our job of promoting more sustainable tourism comes in.

After a week of non-stop meetings in Donibane for this year’s Pescadores Ecotourism Summit, we were free to finally take a look at some of the local sights ourselves!

Most of the Donibane’s buildings are from the late 19th century, and all have dizzying, brightly coloured facades. They are so picturesque that they are the country’s main draw for bachelor parties and famous travel bloggers in the summer.

It is appropriate then, that Donibane hosts the largest number of bars/pubs per capita in Septentrea! There are 4.35 tabernas—tavern/pub—for every 10,000 people. We went on a taberna crawl through Donejurgi Hiribidea—St George’s Street.

Pescadoran tradition dictates you must be given a small snack, a pintxo, with every drink you order—something we came to appreciate as the night went on. Our favourite pintxo was gaxtaviaz—moose head cheese—served on bread. Throughout the night, we drank kalimotxo, red grape wine mixed with kola flavoured soda. We also got to try port, a fortified red wine popular in the Lusosphere. Finally, we had zikiritxe, rebottled rum from Jamaica. The name comes from the neighboring Windish, skrikja, meaning “to shriek.”

This last liquor was accompanied with a curious local tradition, the aoti zikiritxe—literally, “way of (doing) the screech.” Pescadorans hold that anyone who wants to be an honourary Pescadoran must drink a shot of zikiritxe and kiss a cod-fish. We were lucky enough in that the last taberna had fresh cod in the kitchen, so we partook in the local custom.

A couple of locals, in return, paid for our drinks in a show of cross-cultural hospitality. By coincidence, one of them turned out to be Eneko, a local guide who we had already hired to take us on a little tour of the rest of the country.

Speaking about cod, we were surprised to learn about the 1992 Cod Moratorium was still mostly in effect in these waters. we were lucky enough that our pintxos included real fried cod tongues, a local delicacy that is often in short supply. Eneko assures us that these are not illegally obtained by “cod vikings”—a term coined by Albertans to describe Windish and Pescadoran fisherfolk who violate the moratorium—that instead these cod were sustainably caught through recreational fishing.

We awoke the next day with headaches … but Eneko was ready with a traditional breakfast of hirugihara, back bacon smoked over balsam fir; maxaroz, a milk and manoomin porridge flavoured with syrup infused with balsam fir tips; and of course, guarana pulled like espresso taken with condensed milk.

It was then time to hit the road in Eneko’s car. Our first stop was to Placenzia, 130 km away through the winding hills of the Ternua Peninsula. Most visitors ignore the inland route to Placenzia, taking a seaplane instead, but we practice what we preach here at the Slow Foot Movement, so we opted to travel like locals do. And boy were the sights well worth it!

At one point, Eneko stopped the car by a river. His eagle eyes had spotted a herd of migratory woodland caribou—karibua in the local Basque creole—swimming across a river. He further amazed us with the fact that this is actually the southernmost wild herd of the species. The animals were once so common in the forests of what is now Alberta, Indiana and America, but explosive human population growth in the Industrial Revolution pushed their range further and further north. The Pescadores, as well as neighbouring Windmark, are populated sparsely enough that, with good conservation laws, these beautiful creatures have been able to hang on. And yet, it strikes me that most tourists will never see them due to not taking the overland route.

The interior of the country also hosts most of the settlements of the Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqiyik, who came over to the Island of Tamcook after the collapse of the Indigenous Beothuk population in the centuries after the arrival of the Europeans. We got to see one of these villages when we stopped to refuel in a village called Miawpukek, and I took the opportunity to buy a pair of beaded earrings from a local artist and a secondhand Mi’kmaq-English dictionary. Interestingly, the Mi’kmaq lect in the Pescadores is intelligible with Souriquois, spoken across the Gulf of St. Lawrence in Migmagee and Alberta.

When we finally arrived in Placenzia after long hours on the road, Eneko found us a us a boutique hotel called the Oiartzun. Donibane may be the economic and touristy city most known to outsiders, but Placenzia, with its Portuguese colonial architecture, has its own charms. The capital of the Pescadores is known for its beautiful etxe architecture—iconic for the whitewashed walls with painted half-timbering.

We spent a quiet evening in a family-run restaurant that made their own xorixoa, a spiced sausage. We also ordered some firkatel, a Pescadoran take on Windish fish meatballs made from air-dried cod or klippfisk, as well as kokoxa, which are the stewed dewlap of the cod. Eneko encouraged us also to try smoked capelin, which is a staple fish that magically washes up onto the shores of all of Tamcook in the spring.

The next day, we headed to the wharf to go on a cruise. A heritage steamship, the SS Donostia, took us from Donibane all the way over to Mikelon, from where we would eventually get a tour of the Fortuna Islands. Though it was late in the season, Eneko’s sharp eyes helped us spot lots of wildlife! We saw a fin whale, dolphins, a few seals, but none of the famous puffins.

The next day, we got up early to watch the sun rise over the sea as we pulled into the picturesque town of Mikelon. Eneko took us to meet some seals at a sea ranch, where we got to pet a very friendly pup called Xabieron. We also learned that, although seals are native to the Pescadores, they are different from the domesticated ones! Seal hunting is still common, but domestic seals, also known as goons, are native to the Pacific, and were introduced only very recently in the past hundred years.

We also got to watch a local game of pilota, a sport similar to tennis, which is getting more popular in Europea. We also attended an estropadak match off—known locally in Pescadoran Basque as a guitnak from the Mi’kmaq influence. It’s a traditional rowing competition where church parishes compete. The seriousness of a guitnak race is no joke, and Eneko told us about violent village feuds that dominated national discourse until the last century out in the Fortuna Islands. Drinking—for warmth and courage—while rowing out on the high seas was also another issue …

The next morning, we went back on board the SS Donostia and continued the cruise as we circled the more remote islets of the Fortuna Islands. Seeing the coast from the water gave us breathtaking views. In spring and summer, apparently, icebergs can be commonly spotted floating in between the islands.

Worthy of a mention was the onboard lunch on this day, which featured a local take on piperrada. Traditionally a peppery tomato stew, the Pescadoran version includes stewed fucon—goon or seal meat—uses unripe green tomatoes, and ironically, contains no peppers, as they are hard to grow here. We tried to not think of that cute pup Xabieron as we savoured the tender chunks of meat. The stew really warmed us up and we felt we could withstand all of the blustery Atlantic as long as we had it in our bellies.

But of course, the warm lights and bells of Mikelon’s port called us back. We turned in to a little hotel, knowing that the next morning, we would be taking a boat plane back to Plazencia in preparation for our departure for the next country on this grand little Slow Foot Movement tour of ours.

FIELD NOTES

The national and prevailing lect in the Pescadores is Basque. Basque is a Navarrese-based creole, and like most creoles, doesn’t conjugate verbs. It also has the distinction of having adopted grammatical features found in Algonquic languages, such as nominative-accusative alignment—which we also find in English. For these reasons, and also due to the high number of Souriquois, Wolastoqiyik, as well as Windish, Beothuk, and Portuguese words, Navarrese speakers struggle to comprehend Pescadorans, something that baffles Pescadorans to no end. Apart from Basque, most Pescadorans also learn Portuguese, due to the long history of Portuguese rule on the islands.

The original inhabitants of the Pescadores were the Beothuk, followed by Windish settlers. The Pescadores originally referred only to the southern isles and shoreline of Tamcook Island. This territorial strip was licensed off to Navarrese whaling companies by local Windish chieftains. Due to a famine and political turmoil in the 16th century, more land concessions were granted, this time to the Portuguese, who showed little interest in settling the lands themselves and continued to allow for Navarrese mercantile activities in the area. The island is now split with Windmark.

Like in Windmark, the most important resource in the Pescadores was cod. Local stocks collapsed, however, and the transnational Cod Moratorium was implemented across the western North Atlantic. Only recently was the moratorium partially lifted to allow for recreational fishing. With hundreds of thousands facing serious unemployment, the focus has since been to turn to tourism to fill the gaps in the economy.

Interestingly, due to a history of poverty pushing settlers to be resourceful in gathering local seafood, there is still a strong stigma around eating most seafoods except for goons or seals and fish like cod, capelin, and haddock. This odd aspect of Pescadoran foodways is also shared with the Windish. Pork is king, and venison is commonly sourced from deer, caribou, and moose. Whale had a history of being eaten before the 20th century. Recently however, returning diasporans have slowly diversified the local diet, though we were charmed by the fact that calamari was still viewed as a foreignism on local menus.

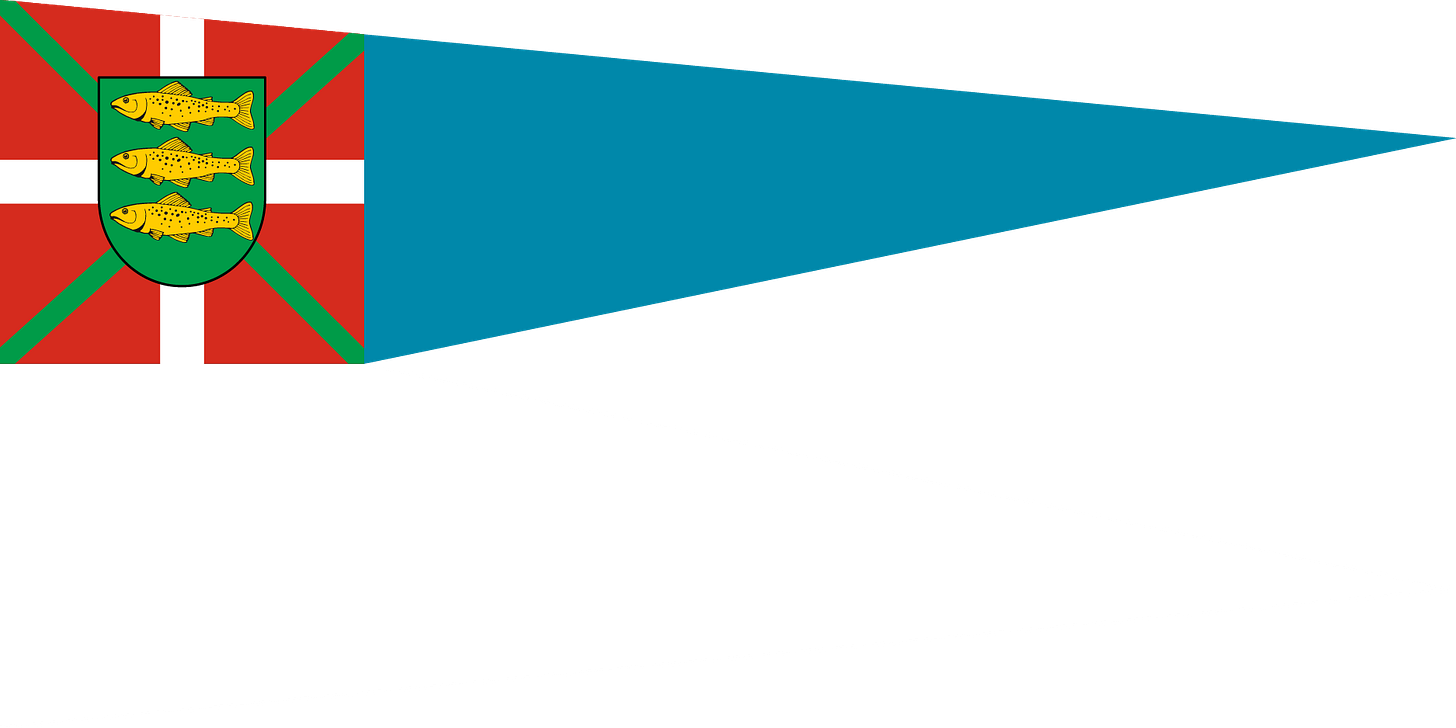

The Pescadoran flag is iconic. Taking elements from the Pan-Navarrese movement common amongst inhabitants of the Secidades and Satanaxes, the flag consists of a double fanion with a white fanion at the bottom, representing peace; and a blue fanion on top, representing the sea; as well as the Navarrese Ikurrina in the canton. The canton is overlaid with the coat of arms of the Pescadores. The three fish represent the first three settlements in the country—Matxaroa on Fogo Island, Mikelon, and Inguratxarra. Locals also attribute the fish to represent the three founding peoples of the nation, the Navarrese, Indigenous Beothuk and Algonquic peoples, and the Windish.

The Pescadores has a relatively multicultural history. Most locals are descended from Navarrese whalers and fisherfolk, but ancestry traced to Algonquic peoples is also common across the general population—though only 5% identify as part of the Wolastoqiyik and Mi’kmaq communities. There is also Windish admixture, particularly in the north, and almost one in ten surnames in the Pescadores are of Windish origin.

A quirky artifact from the Portuguese period is the local practice of the Nkisi epidoxy alongside Roman Catholicism, observed by most Pescadorans. This practice is closely related to the Palo branch of Vooduism, found in the countries of Palmares, Pantanales and Congo. This syncretized form of Palo came via contact between sailors and the territories of colonial northern Brazil, when Pescadorans would come in contact with enslaved and free Guineans. It is common to see Pescadorans worship a peculiar Nkisi effigy in the form of a ship figurehead, called a katamalo, a syncretism that also often takes on the features of the Algonquic mythical hero Glooscap, here known as Kluskape. Offerings to these effigies often consist of tobacco and balsam fir tips—a popular product of the local forests known as zitokon.