Dispatch from TOWAII

Gorging on earth oven meats; surfing Santas; and admiring the Makahiki spirit of a small island nation

Time for a short intermission, fellow travellers! My old friend from highschool, Nainoa ‘Ōpūnuilani, has invited us to his home country of Towaii to celebrate the traditional solstice festival, the Makahiki! During this second quarter of the year on the Haumoanan calendar, locals return to their ancestral villages for as long as possible to celebrate with loved ones. At the invitation of Nainoa, we will be able to not only participate in some of the more local and authentic cultural activities, but also take advantage of the tourism boom that happens during this annual celebration. And for once, we don’t even have to work!

DISPATCH

We arrived in Puuwai on an Air Aloha flight from Montreal. We were lucky that during the holiday season, there are direct flights from this far side of Septentrea. Normally, people in this part of the world have to connect via cities in California and Wakasan with long layovers, taking old rickety Stratocruisers instead of the more modern widebody or double-decker jumbo jets. A romantic vintage plane would have been nice, but Nainoa’s invitation had mentioned a lovely traditional lū’au feast scheduled for the day after we arrived, and we did not want to miss that opportunity.

We arrived late at 02:00 (WTC24 +12) in the morning, or 00:120 in the local time zone (WTC6 +3)—that’s island time for you—but Nainoa was waiting for us at the terminal. He picked us up in his own iconic Tautoru Hikoi, an all terrain convertible sport utility vehicle based on the Skoda Octavia. We almost squealed with joy when we found out it would be our means of transport for the trip!

The capital city of Puuwai, on Ni’ihau Island, is only the second largest city, with 50,000 people. During Makahiki, the number actually halves—shrinks below 25,000! Tradition has it that Towaiians must return to their ancestral villages for Makahiki, which means that huge sections of residents—from roadside hawkers to civil servants—are gone for up to a third of the year.

Nainoa first drove us to the town of Pōleho on the east side of the island. His home stood out from the large vernacular hale wa’a homes—dwellings that fit multigenerational families all under one thatched A-frame roof. “It looks grander than it is,” he warned as we came up the drive way. The house was built by his grandparents and exemplifies the early 20th century form of the kamaaina style, a European influenced home more commonly built in Hawaii, also known for the iconic lānai—a veranda or wraparound porch atop a traditional foundation of lava rocks. “A hundred years old and hardly been retrofitted since,” Nainoa said. “I was the one who put in solar. Before that—just a generator. Can you believe that?”

The next day, we we slept in. It was almost noon when wafts of seared meat woke us up. Towaiians still use the traditional imu cooking method for feasts or just big meals. It consists of using an earth oven set up in the garden to simultaneously roast and steam meats and vegetables. Apart from festivals, most Towaiians get together with the community for a big lūʻau at the end of each anahulu—the ten-day week used here. This is when pork is eaten the most. Most other days, fish and seafood are more commonly eaten.

As Nainoa brought us over to the communal table where his family awaited, he explained that the many bowls of purple gloopy stuff is known as poi, which accompanies every meal. In Towaii, poi is commonly made from taro, though in Hawaii, other corms and tubers are also mashed into the creamy paste form—mashed potato is just “potato poi.” We were served a thicker and more sour tasting kind of fermented poi, which went so well with the roasted kālua pork fresh from the imu. Beef short ribs known as pipikaula and lomi ʻōʻio—a paste from raw freshly caught bonefish—were also served. We scarfed all this down with various stews, all known as lūʻau, as they all feature the leaves of young taro plants stewed in coconut milk. Vegetarian in its simplest form, the stew can also be spruced up with a variety of seafood. The stew is so common at these functions that it’s how the lūʻau feast got its name!

Our dishes were well dressed with all the traditional seasonings— various seaweeds known as limu; dried and crushed shrimps; and inamona, roasted and crushed candlenut. Very few foreign additions have made it to the tables of Towaiians, as they prefer to stick to their traditional foodways. Limes, soy sauce, and banana ketchup seem to be an exception though.

By the time the haupia—pudding cake made from coconut milk and pia (Tacca leontopetaloides) starch was offered to us for dessert, we were ready to pass out, but Nainoa forbade sleep. “Tonight, we conquer time—that so called jet lag—with merrymaking,” he said. “Besides, you’re about to replenish your mana—your energy.”

That’s when it became time for the kava. Kava culture here is found in backyards, but also in ceremony, while in Hawaii, there is a thriving kava bar scene, which has even spread to California and other parts of the Western world.

We gathered in Nainoa’s uncle’s backyard and sat around him as he prepared the drink in a large bowl. This quintessential Polynesean drink is a staple at social functions and is surprisingly not alcoholic—at least not in its fresh form. It took a couple of rounds to feel the calming but energizing effects, and once it hit, it became clear to us outsiders why it is so cherished here. We relaxed and words began to freely flow. It felt like we socialized for hours, and by the end of the night, we were more than acquainted with all of Nainoa’s family and friends.

Then we caught up on some sleep. The hours in this part of the world are literally longer, but it felt like we only caught a short snooze. Nainoa had us up bright and early so we could make the first car ferry out of town the next day. Before we knew it, we were already docking in the port of Tapa’a, Towaii’s largest city. It’s located on the larger Taua’i Island, which is, yes, the namesake of the kingdom itself. And it’s easy to see why! It is a gorgeous and highly impressionable island. Vistas sprawled out before us at every corner and turn of the road.

Nainoa arranged a tour of one of the island’s oldest pond field systems, known as a lo’i. Essentially, they use earthen channels and stone dams to transport water from upland and wetter areas into drier lands while all the way irrigating terrace farms. The fields and channel margins are sheltered by crop-yielding trees. Towaiians have been growing taro (Colocasia esculenta) in this way since their arrival on these islands. On Ni’ihau, other staples like ti (Cordyline fruticosa) and kumara (Ipomoea batatas) are more common—the latter being an early introduction from Crucea! We were also impressed to learn how the lo’i may share its roots with the paddy fields of Ruson and Tayen Island, home to the ancestors to all Polynesean peoples—guess the rice just got left behind!

The lo’i system also incorporates fish ponds. As the water travels down the terraces, it arrives in lowland and coastal ponds known in Towaii as loto i’a. These vary in salinity and farmers grow algae in them to feed paddy goby (Lentipes concolor), mullet (Mugil cephalus), milkfish (Chanos chanos), and Polynesean perch (Kuhlia sandvicensis). We were impressed to see how lava rock walls are used to enclose reef flats along the shore, with access controlled by sluice gates in channels and streams. Our guide also explained how the nene or Polynesean goose (Branta sandvicensis) was domesticated by early Towaiians due to their preference to feed in these ponds.

We drove back towards Tapa’a as the sun was setting and noticed how lively it was all along the road. Nainoa pulled over for us to watch some locals compete in friendly lua competitions. Practicing this traditional form of martial arts is a must during Makahiki. Nainoa was even challenged to a match by three youth. “Normally, you don’t land on your back so much,” he explained as he retreated back to us, trying not to limp. He was in better spirits later when we drove into the city and came across a hula performance in a square. “Even in our high school days, I was always more for the arts, remember?” he said. But no encouragement seemed to help get him on stage to perform with the other dancers.

A day later and we were in the picturesque town of Hanalei, the host for the World Surfing League (WSL) Big Wave Competition this year. It’s renown for year round good surfing conditions and a mix of traditional landscapes and modern tourism amenities. Its haven of a bay was perfect for some much needed recreation and rest. We were delighted to learn it would be home for the rest of the trip!

Before we got on our sunscreen, Nainoa had already convinced us to not just to watch others surf, but also sign up for the Surfing Santas competition for amateurs. He pulled out our hats from the car trunk and led us to a free lesson on the beach. We trained to the tunes of a live band that performed all sorts of hits, from classics played with the traditional mouth harp known as the ūkētē to strummed fusion songs played with the ukulele. When we finally managed to stay up on the boards without falling, we were ready.

But of course, of all places to compete with amateurs, this was not the best place to begin. I’ll just say we never made it onto the rankings, but of course, Nainoa did! With a medal dangling from his neck, he served us some conciliatory koto, hot cocoa with cocoa pulp, and tōʻelepālau, a mash of kumara and ube mixed with coconut cream and served cold. We then watched the professional matches. In the finals, a Tasmanian took to top prize for the open category, a Vasuguayan for the men’s category, and to everyone’s pleasure, a Towaiian won the women’s category.

The next morning, we all walked down to the pier jutting into the bay and watched the sun rise. “How lucky you are to roam and fall into place among such beauty,” Nainoa said. Truly, we nodded.

FIELD NOTES

The islands of Towaii, together with those of Hawaii, are part of the larger archipelago or island arc now known as the Ko’alau Islands—historically the Sandwich Islands. They are volcanic and were formed from an active underwater magma plume known as the Ko’alau Hotspot, responsible for the creation of the 6,2000 km long seamount chain that stretches all the way to Kanchata!

The most fascinating natural feature of the country is Mount Waiʻaleʻale, whose name means “overflowing water.” It is over 1,500 m high and receives an average rainfall of 9,500 mm per year. This shield volcano is the one of the wettest spots on earth. Its runoff feeds into Alata’i Swamp in a plateau below, which is a montane wet forest that was confused for a swamp by early European biologists due to how boggy it is. The forest is a refuge for extreme biodiversity, preserving species that have disappeared from the broader Ko’olau Islands.

The national language of Towaii is Towaiian, a Malayo-Polynesic lect closely related to Hawaiian. It has far less loanwords than its counterpart, which includes many loans from English, Spanish, Portuguese, Japanese, Kantonese, Nahuatl, Tagalog, Qichwasim etc. As such, Towaiian is said to be intelligible to Hawaiian speakers, but harder vice versa. To understand why this is, we must look at the political maneuverings of the ruling Kekaulite Dynasty, who originally hail from Oahu Island in Hawaii. They had inherited the crown of Towaii through marriage in the early 19th century.

The mōʻī or king Taumualiʻi I had repelled attempts at annexation by Hawaii through military tact, but his son, Prince Humehume—who had sailed widely with Europeans and Americans—astutely sought an 89 year deal to gain protectorate status under the British Empire, similar to the treaties negotiated in western Thulea to contain the Americans. During Humehume’s reign, the kingdom was closed off to foreign contact except with the British. As Hawaii underwent extensive Westernization, Towaii stayed largely traditional. Its local lect became distinct from that of Hawaii, which underwent consonant shifts—for example, Makahiki is pronounced locally as Makahiti, while Towaii is known as Kauaʻi in Hawaiian.

Towaiian is written in the Kohau script, a featurary that works like the Hanmunja of Goryeo. The name comes from the Rapanuian kohau ta’u ika, “lines of years and fish.” It was originally used in Rapanui to record casualties of war, with the deceased being euphemistically known as fish. It was first used as an ideatary, but in Hawaii it was reformed into a featurary. Interestingly, the people of Rapanui would later abandon writing in Kohau, opting for the Avoiuli script of Aotearoa instead.

The adoption of the Kohau script in Towaii was accompanied by the spread of Hauniuism, a faith originating in Aotearoa, but which syncretized Christianity with traditional Polynesean mythologies. Despite late adoption, the religion of Hauniuism found much more popularity in this small kingdom than almost anywhere else in Polynesea, with 94% of the population practicing it, compared to 47% in Hawaii—on account of Christian and Buddhist minorities. The people here are also said to be more pious than Hawaiians.

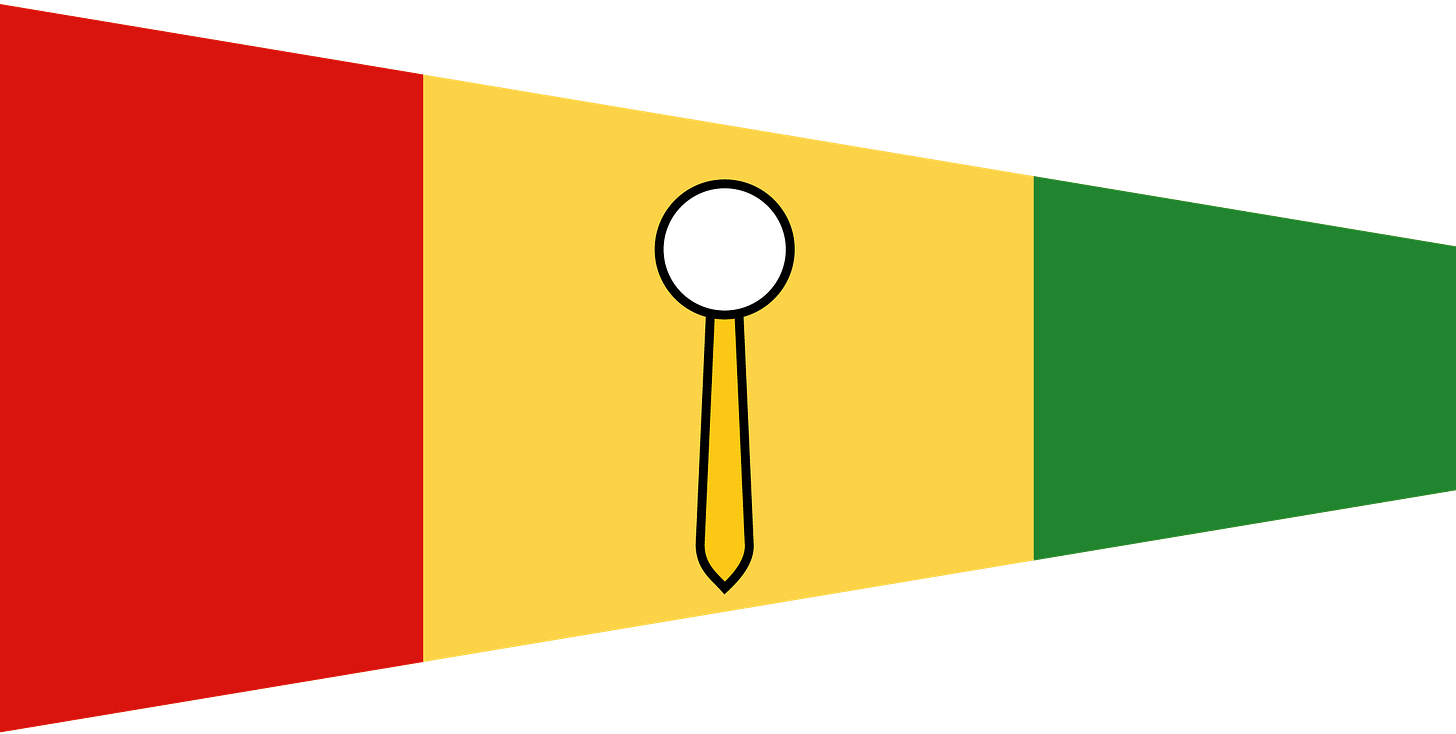

Did you know Towaii’s flag represents the symbol of power of all of the Ko’olau Islands? The symbol at the center is a pūloʻuloʻu, a staff covered at the end with bundles of kapa. The bark cloth there represents the ancestral spirits of a ruler. The round shape the cloth is fashioned into represents a star, a symbol of po, “heaven”, where the ancestors dwell. Hauniuan temples in Towaii, called heiau, are decorated with a pūloʻuloʻu in addition to the prayer poles found in other countries. The colors of the flag represent green for the land, gold for the country’s bright future, and red for the blood spilled defending the kingdom’s sovereignty and independence.